My Trip to Fort Peck

When we entered Poplar, Montana, a billboard advertising the dangers of meth was our welcome sign. And then a billboard for stopping violence against women. Then another billboard advocating the correct usage of bath salts. I expected the Fort Peck Indian Reservation to have its fair share of problems, but I never expected them to be so blatantly in my face. And then there were the white crosses. I think those disturbed me the most. They were dotted throughout the highway, signifying those who had lost their lives. Many of them were probably young. Fresh flowers draped over some of the crosses, the deceased still being mourned.

And then we were at the heart of the town, or what Wikipedia claimed was called “Stab City” by the locals. But all I saw were empty dusty roads and worn out buildings. The people must’ve been in hiding. It was as uneventful ride until we finally reached Fort Peck, where a big wooden cutout of a cowboy greeted us. It was odd, I thought, to have a big ol’ cowboy sign in the middle of an Indian reservation. Not to mention the many churches scattered throughout the land. Beside the many advertisements for casinos, I would’ve never guessed I was where the Sioux and Assiniboine Native Americans inhabited. It was a land stripped of its roots. A land full of Native Americans whose unique culture was drifting away.

“Can you believe that only four people on this reservation can speak their native tongue?” commented Dr. Kevin.

Actually, now that I was here, I could believe that.

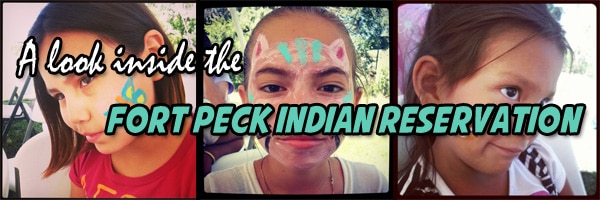

The next day, Dr. Kev in told us that we would be advertising Kids’ Fun Day by holding some signs on the main street. I thought he was kidding. How are hundreds of kids going to attend this event if all we’re doing is holding up a few signs? But we did as commanded. There Katie and I were, holding a sloppy sign constructed out of a plastic table cloth, waving it at the occasional car. Many passed by us, giving us a quick wave or a nod, and only a few made the turn towards the festivities. After an hour or so of waving signs at drivers, we headed back to camp.

in told us that we would be advertising Kids’ Fun Day by holding some signs on the main street. I thought he was kidding. How are hundreds of kids going to attend this event if all we’re doing is holding up a few signs? But we did as commanded. There Katie and I were, holding a sloppy sign constructed out of a plastic table cloth, waving it at the occasional car. Many passed by us, giving us a quick wave or a nod, and only a few made the turn towards the festivities. After an hour or so of waving signs at drivers, we headed back to camp.

I guess I underestimated the power of connections and the close-knit Native American community. Word spread like wildfire and we returned to find a bunch of screaming, laughing, smiling kids. I had to dodge them to get into the Chiropractic office, where the face paint was. Katie and I returned outside to claim our table and soon a line of kids formed. And that line didn’t stop until Kids’ Fun Day was over. Honestly, I didn’t see much of the extravaganza. I missed Dr. Ed getting soaked in the dunk tank, didn’t get to wear the penguin bracelets that were waved at my face as I painted cheeks, and my hair wasn’t sprayed with glitter. Although, I’m glad I didn’t mess with my hair. With the mediocre shampoo they gave out at the motel, it would take days to get the glitter out. I did, however, get to have one of Dr. Sabrina’s delicious mini cupcakes and make a few keen observations of the people of Fort Peck.

As I worked at turning a girl into a cat with pink paint, an older Native American struck a conversation with me. He told me about what the street looked like before the economy crashed. How there were food stores and a bookstore. A nice motel and a restaurant. But all of that’s gone. All that remains now are the skeletons of the past. Empty buildings, except for a movie theatre and Chiropractic office ready to be used. He then went on to say how he got a scholarship to go to a college in Massachusetts, but it was too different. Too foreign. He returned to Fort Peck where he remains today.

It’s hard to be a Native American, I realized. Most big opportunities lie outside of the reservation, but many don’t take the risk. They choose to stay where they are, despite the terrible conditions. It’s their home, where their people are. But unlike immigrants who have a country they could return to, these Native Americans have a piece of unfertile land they were forced into, where they were beaten into acting like white people until much of their native culture was forgotten. Suddenly I realized how  important us being here was. Little by little, child by child, we were dropping seeds of hope. Maybe one day these seeds would sprout. Maybe one day a new father will decide not to binge on alcohol and instead be there for his daughter. Maybe one day a teenager will choose not to take his life, because he doesn’t feel so abandoned.

important us being here was. Little by little, child by child, we were dropping seeds of hope. Maybe one day these seeds would sprout. Maybe one day a new father will decide not to binge on alcohol and instead be there for his daughter. Maybe one day a teenager will choose not to take his life, because he doesn’t feel so abandoned.

I finished with my obscure lion head and went on to the next child. Hair was covering her cheek and so I asked that she tuck it behind her ear. And then what was revealed to me were strands of hair pure white from rows and rows of lice. It wasn’t the occasional lice or two hopping around a child’s head. It was clear that this problem wasn’t attended to for a long time. Her parents must’ve been too poor to buy her special shampoo. Or maybe she was just ignored. With this sad inquiry in my mind, I placed a purple butterfly on her face. At least I got a smile out of her. She left and a boy took her place.

“Can you write ‘WC’ on my face?”

“Why?” I asked. “What does it stand for?”

He looked at his friend before responding, “Can you just paint it?”

And so I painted the letters. Twice. His friend wanted the same thing. After they left, the elder man said to me, “You know what that means? It’s a gang here.” I was horrified. They looked only nine and instead of aspiring to become astronauts or presidents, they wanted to be part of a gang. What was scary was the fact that the morbid dream could easily become a reality. And frankly, kids here seemed to be punched in the face with reality earlier than most kids.

“I almost saved a person’s life,” said a vivacious little eight year-old as we were cleaning up after Kids’ Fun Day had resided.

“Oh really?” I said. “How?”

She ran her finger through the white fur of a mutt. “Well me and my friend were walking and we noticed this guy lying here on the street. He was dying!”

This was not the cute story I was expecting.

“He looked like he was already dead, but my friend checked to see if he was breathing. I was gonna give him mouth to mouth but then someone came and called the ambulance. But I think he died afterwards, so we almost saved his life!

I didn’t know how to react to that. Did she witness a man ODing right in front of her? I muttered a “wow” as I tried to chase away the thought in my head.

But the thought didn’t leave me. It was just added to the many sad revelations I made during that trip. How it would take them two hours just to be able to get the proper  school supplies they needed. How many were left jobless, bored out of their minds, and resorted to drugs and alcohol for entertainment. I found out why there weren’t many people walking the streets in daylight. They came alive at night. Bars I hadn’t noticed before lit up the streets, paired with the flashing lights of police cars as they tried to stop a fight. Everyone loves a wild night or two. But if there isn’t anything to look forward to besides where the next party is, what is there to live for? What is a life without aspirations?

school supplies they needed. How many were left jobless, bored out of their minds, and resorted to drugs and alcohol for entertainment. I found out why there weren’t many people walking the streets in daylight. They came alive at night. Bars I hadn’t noticed before lit up the streets, paired with the flashing lights of police cars as they tried to stop a fight. Everyone loves a wild night or two. But if there isn’t anything to look forward to besides where the next party is, what is there to live for? What is a life without aspirations?

I watched the rolling scenery of plateaus from out my car window. Katie had her hands on the wheel, keying in on a metal trailer tucked away on the grassy plain. “You know, I’ve seen ghetto before,” she said. “But at least people can escape to another city. Take the highway for fifteen minutes and be somewhere. But here, where is there to go? How can you escape something that surrounds you for miles in every direction?”

And so they are stuck. Stuck between first world and third world conditions. They are in a fourth world—a gritty mix of first world issues such as drugs and the overconsumption of fast food, blended in with the poverty level of a third world country. Change is not going to happen fast. It took decades and decades to beat down the Native Americans’ spirit, and it will take a long time to bring back that spirit—to reignite that inner warrior within them. After attending this trip, I now have a greater understanding of Love Has No Color’s mission. The simple act of returning year after year for the children does something to them. It sparks something. Hope. And sometimes that’s all they need to decide that they’re not going to give up, and walk a better path.

– Rebecca from TNR