Lucky Child

When I was younger, my mother’s past had been a mystery to me. I knew she was in a war, but I was under the assumption that she escaped it by running through the jungle. In one of my early journals, I can still find the short entry written by the seven year-old me about my mother’s journey, with a rough sketch down below of her making friends with a leopard and a monkey. It wasn’t until my early teens that I began to piece together my mother’s broken past.

I was at that stage everyone went through during their awkward teenage years. The unnecessary angst. The grim realization that life sucked. One day as I was cleaning the dining room table, I had voiced this opinion out loud.

“I hate my life!” I said as I scrubbed away at the mahogany. “I wish I had never been born!”

My mother, who was busy with some Cambodian dessert, stopped what she was doing and looked at me. The look alone made me want to retract my words. On her face was a quiet anger, expressed only in the slight darkening of her eyes. She dropped her spatula and came to me with a pointed finger.

“I don’t want to ever hear those words come out of your mouth again,” she said in a low growl. “Not until you know what it feels like to work from sun up to sun down starving, not knowing whether or not you’ll live till the next day. You don’t know how lucky you are to live the life you live!”

I was speechless. The only words I could utter was a “sorry” as I bent my head in shame. The gesture masked the shock I received from her words. I realized that day that there was a huge part of my mother I never knew.

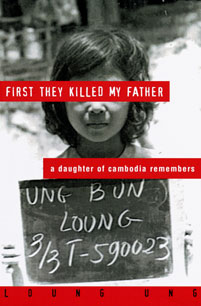

As fate would have it, my teacher assigned us Children of the River, a book about the Cambodian genocide. It led me to discover the most influential book of my life: First They Killed My Father. It was in this book that I learned the suffering my mother had to endure—the horrors a fourteen year-old girl should never witness. Should never experience.

As fate would have it, my teacher assigned us Children of the River, a book about the Cambodian genocide. It led me to discover the most influential book of my life: First They Killed My Father. It was in this book that I learned the suffering my mother had to endure—the horrors a fourteen year-old girl should never witness. Should never experience.

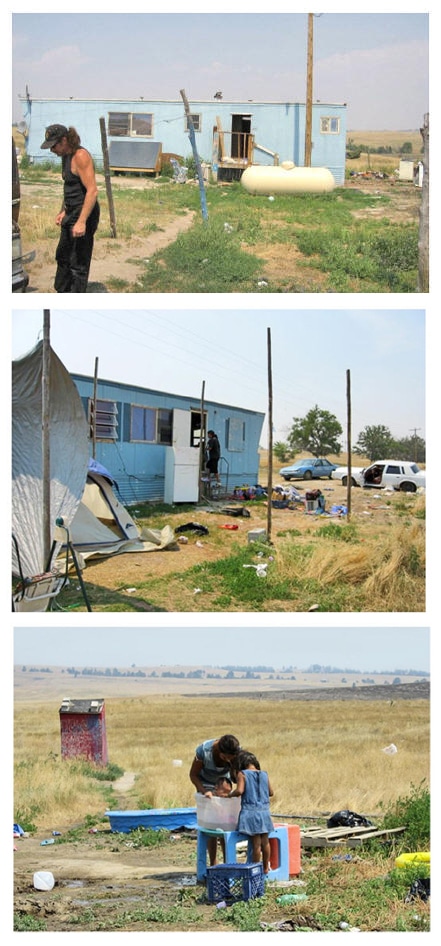

But it happens. And it happens closer than you think. You don’t need to go to some exotic country to see hopelessness. You just need to look in your backyard. At the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana, the future seems so bleak to children that suicide has become a common occurrence. Broken homes, substance abuse, bullying—these issues have woven into what should be happy childhoods. Three out of four children live in poverty here, with the unemployment rate over fifty percent.

“When people get bored here from watching TV, they smoke weed or get drunk,” commented a fifteen year-old. “There’s nothing to do here.” This perhaps caused thirteen year-old Chelle Rose Follette to accidently take her own life. In an intoxicated state, she had a venomous fight with her parents and fashioned a noose out of her pajamas. Her mother believed Chelle wanted to scare them, but it ended as a tragic accident.

I sat there, in the comfort of my office chair, with the hum of the printer resounding in the background, reading those reports. In the World Project archives I came across a three-year old news article describing how tribal leaders had declared a state of emergency when five middle schoolers committed suicide with twenty others reported to have attempted to. I was shocked, but most notably there was a sadness that vibrated within me. How desolate their lives must be to contemplate suicide at such a young age. While I spent my early teenage years worrying over tests and whether or not my clothes were in style, these kids were faced with a grim reality some no longer wanted to partake in.

And so, my mother’s words find their way back to me. “You’re lucky to live the life you live.”

During one of the more welcoming days of spring, I sat outside with my boyfriend as we enjoyed Nestle Drumsticks. As my attention was on a flitting bird, my boyfriend was intrigued with the ice cream he had in his hand.

“You know how lucky we are?” he said out of the blue. “You know how many kids in the world will never experience this? You know, one out of two children is born into poverty. We could have been born anywhere, but we ended up here. We’re so lucky.”

Love Has No Color is an initiative to create more lucky people in the world. To allow hardworking girls to receive scholarships so that they can pursue higher education, to let teens shoo away their boredom with the latest Johnny Depp film playing at the theater, to allow little boys to get their race cars for Christmas and little girls their dolls. To have more children spend their summer days enjoying Nestle drumsticks. Because luckiness comes from the hard work of people. Let’s have more lucky people in this world.

~ Rebecca from TNR

Sources:

http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/03/21/ap-enterprise-indian-youth-suicide-crisis-baffles/*NOTE: As of 2024, this article is no longer accessible.

http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2013-03-21/local/37904086_1_sequester-tribal-leaders-million-in-additional-cuts *NOTE: As of 2024, this article is no longer accessible.